Conventional wisdom has it that the entry of the United States into World War II caused the end of the Great Depression in this country. My variant is that World War II led to a "glut" of private saving because (1) government spending caused full employment, but (2) workers and businesses were forced to save much of their income because the massive shift of output toward the war effort forestalled spending on private consumption and investment goods. The resulting cash "glut" fueled post-war consumption and investment spending.

Robert Higgs, research director of the Independent Institute, has a different theory, which he spells out in "Regime Uncertainty: Why the Great Depression Lasted So Long and Why Prosperity Resumed After the War" (available here), the first chapter his new book, Depression, War, and Cold War. (Thanks to Don Boudreaux of Cafe Hayek for the pointer.) Here, from "Regime Change . . . " is Higgs's summary of his thesis:

I shall argue here that the economy remained in the depression as late as 1940 because private investment had never recovered sufficiently after its collapse during the Great Contraction. During the war, private investment fell to much lower levels, and the federal government itself became the chief investor, directing investment into building up the nation’s capacity to produce munitions. After the war ended, private investment, for the first time since the 1920s, rose to and remained at levels sufficient to create a prosperous and normally growing economy.

I shall argue further that the insufficiency of private investment from 1935 through 1940 reflected a pervasive uncertainty among investors about the security of their property rights in their capital and its prospective returns. This uncertainty arose, especially though not exclusively, from the character of federal government actions and the nature of the Roosevelt administration during the so-called Second New Deal from 1935 to 1940. Starting in 1940 the makeup of FDR’s administration changed substantially as probusiness men began to replace dedicated New Dealers in many positions, including most of the offices of high authority in the war-command economy. Congressional changes in the elections from 1938 onward reinforced the movement away from the New Deal, strengthening the so-called Conservative Coalition.

From 1941 through 1945, however, the less hostile character of the administration expressed itself in decisions about how to manage the warcommand economy; therefore, with private investment replaced by direct government investment, the diminished fears of investors could not give rise to a revival of private investment spending. In 1945 the death of Roosevelt and the succession of Harry S Truman and his administration completed the shift from a political regime investors perceived as full of uncertainty to one in which they felt much more confident about the security of their private property rights. Sufficiently sanguine for the first time since 1929, and finally freed from government restraints on private investment for civilian purposes, investors set in motion the postwar investment boom that powered the economy’s return to sustained prosperity notwithstanding the drastic reduction of federal government spending from its extraordinarily elevated wartime levels.

Higgs's explanation isn't inconsistent with mine, but it's incomplete. Higgs overlooks the powerful influence of the large cash balances that individuals and corporations had accumulated during the war years. It's true that because the war was a massive resource "sink" those cash balances didn't represent real assets. But the cash was there, nevertheless, waiting to be spent on consumption goods and to be made available for capital investments through purchases of equities and debt.

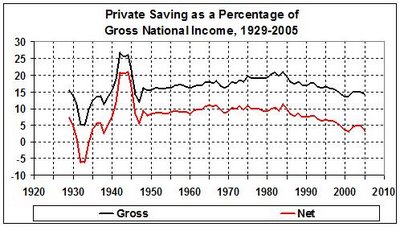

It helped that the war dampened FDR's hostility to business, and that FDR's death ushered in a somewhat less radical regime. Those developments certainly fostered capital investment. But the capital investment couldn't have taken place (or not nearly as much of it) without the "glut" of private saving during World War II. The relative size of that "glut" can be seen here:

Derived from Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts Tables: 5.1, Saving and Investment. Gross private saving is analagous to cash flow; net private saving is analagous to cash flow less an allowance for depreciation. The bulge in gross private saving represents pent-up demand for consumption and investment spending, which was released after the war.

World War II did bring about the end of the Great Depression, not directly by full employment during the war but because that full employment created a "glut" of saving. After the war that "glut" jump-started

- capital spending by businesses, which -- because of FDR's demise -- invested more than they otherwise would have; and

- private consumption spending, which -- because of the privations of the Great Depression and the war years -- would have risen sharply regardless of the political climate.

I happened upon your blog post that deals with my ideas about why the depression lasted so long and about the way in which the war related to the genuine prosperity that returned in 1946 for the first time since 1929. I appreciate the publicity, of course. I suggest, however, that you read my entire book, especially, with regard to the points you make on your blog, its chapter 5, "From Central Planning to the Market: The American Transition, 1945-47" (originally published in the Journal of Economic History, September 1999. I show there that the "glut of savings" idea, which is an old one, indeed perhaps even the standard theory of the successful postwar reconversion, does not fit the facts of what happened in 1945-47.Here is my reply of 10/12/06:

I apologize for the delay in replying to your e-mail about my post... Your book, Depression, War, and Cold War, has not yet made it to the top of my Amazon.com wish list, but I have found "From Central Planning to the Market: The American Transition, 1945-47" on the Independent Institute's website (here). If the evidence and arguments you adduce there are essentially the same as in chapter 5 of your book, I see no reason to reject the "glut of savings" idea, which is an old one, as I knew when I wrote the post. But, because it is not necessarily an old one to everyone who might read my blog, it is worth repeating -- to the extent that it has merit.I will further update this post if Mr. Higgs replies to my note of October 12, 2006.

At the end of the blog post I summarized the causes of the end of the Great Depression, as I see them:World War II did bring about the end of the Great Depression, not directly by full employment during the war but because that full employment created a "glut" of saving. After the war that "glut" jump-startedIn the web version of chapter 5 of your book you attribute increased capital spending to an improved business outlook (owing to FDR's demise) and (in the section on the Recovery of the Postwar Economy, under Why the Postwar Investment Boom?) to "a combination of the proceeds of sales of previously acquired government bonds, increased current retained earnings (attributable in part to reduced corporate-tax liabilities), and the proceeds of corporate securities offerings" to the public. It seems that those "previously acquired government bonds" must have arisen from the "glut" of corporate saving during World War II.

- capital spending by businesses, which -- because of FDR's demise -- invested more than they otherwise would have; and

- private consumption spending, which -- because of the privations of the Great Depression and the war years -- would have risen sharply regardless of the political climate.

What about the "glut" of personal saving, which you reject as the main source of increased consumer demand after World War II? In the online version of chapter 5 (in the section on the Recovery of the Postwar Economy, under Why the Postwar Consumption Boom?) you say:The potential for a reduction of the personal saving rate (personal saving relative to disposable personal income) was huge after V-J Day. During the war the personal saving rate had risen to extraordinary levels: 23.6 percent in 1942, 25.0 percent in 1943, 25.5 percent in 1944, and 19.7 percent in 1945. Those rates contrasted with prewar rates that had hovered around 5 percent during the more prosperous years (for example, 5.0 percent in 1929, 5.3 percent in 1937, 5.1 percent in 1940). After the war, the personal saving rate fell to 9.5 percent in 1946 and 4.3 percent in 1947 before rebounding to the 5 to 7 percent range characteristic of the next two decades. After having saved at far higher rates than they would have chosen in the absence of the wartime restrictions, households quickly reduced their rate of saving when the war ended.That statement seems entirely consistent with the proposition that consumers spent more after the war because they had the money to spend -- money that they had acquired during the war when their opportunities for spending it were severely restricted. Not so fast, you would say: What about the fact that "individuals did not reduce their holdings of liquid assets after the war" (your statement)? They didn't need to. Money is fungible. If consumers had more money coming in (as they did), they could spend more while maintaining the same level of liquid assets -- because they had a "backlog" of saving. Here's my take:

- Higher post-war incomes didn't just happen, they were the result of higher rates of investment and consumption spending.

- The higher rate of investment spending was due, in part, to corporate saving during the war and, in part, to individuals' purchases of corporate securities and equities.

Granted, business and personal saving during World War II was not nearly as large in real terms as it was on paper -- given the very high real cost of the war effort. But it was the availability of paper savings that strongly influenced the behavior of businesses and consumers after the war.

- At bottom, the wartime "glut" of personal saving enabled the postwar saving rate to decline to a more normal level, thus allowing consumers to buy equities and securities -- and to spend more -- without drawing down on their liquid assets.

Perhaps I am misinterpreting the evidence you present in chapter 5. And perhaps there is more in other chapters of your book that I should take into account. I will be grateful for a reply, if and when you have the time.